Explore Brighton Museum’s flat textile collections acquired by the Fashioning Africa project.

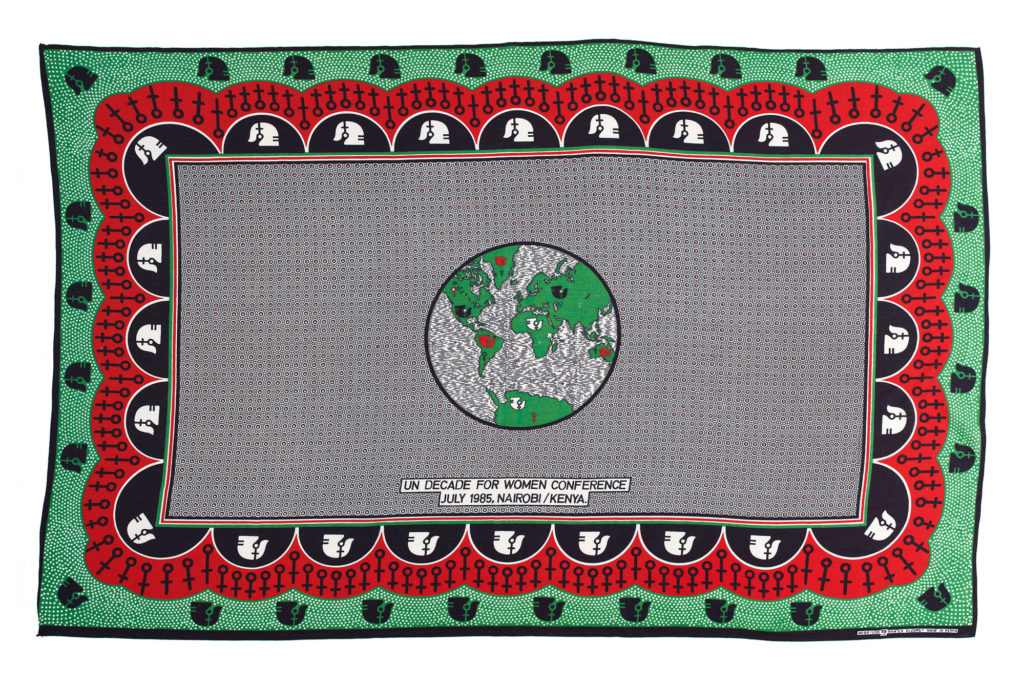

Textiles form an important part of the new Fashioning Africa collection. There is a long rich history of weaving, printing, dying, embellishing and repurposing textiles throughout the African continent and the new collection showcases diverse styles, techniques and practices as seen in post-1960s textiles produced in African countries and the UK African diaspora.

Collected examples include textiles that are culturally-specific, such as the ‘Neck of elep with a line’ design shirt from the Jóola community in Senegal, textiles produced and worn over a broad geographic area like shweshwe (German cloth) from southern Africa and aso-oke cloth from Nigeria, and textiles that have become global signifiers of a pan-African identity, such as wax print and dashiki.

Some of the collected textiles are cloths made to be worn as a wrap or pair of wrappers, or to be used as accessories, for example kangas from East Africa, Basotho blankets from southern Africa, and kente cloths from Ghana. Others are examples of material that would be used to make tailored garments, or pieces of material, for example strips of fabric that would be sewn together to make up a cloth. Examples include both handwoven and mass-produced pieces.

The collected textiles demonstrate the evolution of textile design and manufacture over time, according to everchanging tastes, identities and fashions. Examples include classic styles and techniques, as well as innovative contemporary pieces. These demonstrate some of the ways in which textile production and taste have developed as well as the impact of new technologies. A 2018 example of an aso-oke textile demonstrates this: it is made using a design and technique which are over 120 years old, but also features a contemporary silhouette and layers of embellishments applied using new technology.

Given the extraordinary range and diversity of textiles produced in African countries, the examples collected by Brighton Museum can only provide a limited insight into post-1960 textile production and consumption. Nevertheless, given the relative absence of textiles of this period in museum collections, we hope that these might provide useful starting points for considering how wider social, political, cultural and economic changes have been reflected in the making and wearing of textiles in African countries in the post-independence era.

Object photographs courtesy of John Reynolds