Between 2015 and 2019 the Fashioning Africa team collected over 400 items for Brighton Museum’s permanent collection. The Collecting Panel decided to focus on ten key themes to guide which objects were acquired for the collection.

Political

Textiles and dress not only reflect wider political contexts but can be, in themselves, inherently political. This is apparent in some of those collected through the project. Acquisitions include examples of kanga (an east African textile) used as political propaganda, for example a pair given out to supporters as part of election campaigning by the Jubilee Party in Kenya’s 2017 general election. Also, in the form of T-shirts used to communicate political messages such as those promoting the election of Nelson Mandela as president of South Africa. Politics is also evident in the customised sweatshirt of Charles Makhuya, a guerrilla / freedom fighter with the Zimbabwe People’s Revolutionary Army. Worn in the 1970s, the political associations of the sweatshirt remain so contentious in Zimbabwe that, until recently, it could not be shown in public.

Influences

Textiles and dress also reflect interactions between different ideas and styles. In many African countries, the post-independence era was a period in which new political identities were being established and new cultural modes experimented with. The photographs of Rachidi Bissiriou, Hamidou Maiga and Ibrahima Sanlé Sory, for example, reveal that the music and styles of the 1960s and 70s were as evident in Kétou, Bamako and Bobo-Dioulasso as in London. Styles and materials travelled in different directions. The Sapeurs of Kinshasa and Brazzaville, documented through the photography of Daniele Tamagni, reinvented the look of early 20th century Parisian fashions, initially as part of an anti-colonial politics. Designer Folashade ‘Shade’ Thomas-Fahm combined western silhouettes with Nigerian fabrics to produce garments for the modern, urban woman which offered a uniquely Nigerian aesthetic. Moving in the other direction, a two-piece outfit worn by Lou Taylor in 1976 combined artisan-produced adire fabric from Lagos with the fashion designs of London-based designer Bill Pashley.

Textile Examples

While the Collecting Panel recognised that Brighton Museum’s historic collection of textiles made in African countries was strong, they noted that it lacked examples of some important ‘classic’ textile techniques and did not reflect post-colonial practices. On the panel’s advice and in consultation with weavers and specialists, the museum acquired examples of kente cloth produced in the Ewe region of Ghana, as these are less well represented in museum collections. Adire, an indigo-resist dyeing technique, also became an active area for collecting, with older examples matched with new pieces by designers such as Eredappa Hart and Amaka Osake. Through the efforts and expertise of panel member Edith Ojo, aso-oke, hand-woven cloth made in strips, is now well represented in the collection. Southern African textile forms, for example shweshwe prints and Basotho blankets, were also acquired.

Production, Manufacture and Upcycling

Panel members were keen that the museum collected items which revealed the process of making textiles. Documenting how things were made and worn was an important part of the collecting process, and many of the pieces acquired are accompanied by detailed notes, photographs, film and oral testimony. The collection also reflects the global production of mass-produced textiles for the African market, including printed fabrics made by ABC in the UK, GTP and Woodin in Ghana, Da Gama in South Africa and cheaper fabrics made in China. In terms of process, acquisitions included examples of equipment such as a weaving kit used to make hand-woven kente by Ewe weavers in Ghana. The panel was also interested in the creative reuse of textiles and materials. This is evident in three pairs of sandals made of tyre rubber collected in Kenya. The creative use of ‘thrifted’ garments is also apparent in a set of garments styled by Kenyan creatives 2ManySiblings and in a customised suit adapted by South Africa-based collective The Sartists.

Identity

Clothing is an important tool in communicating identity. Colonial-era collecting focused on collecting garments which reflected perceived ‘group’ identities (for example, Xhosa or Yoruba). Panel members felt it important that new collecting should focus on individual identities. These are especially apparent in the range of studio portraits acquired through the project, for example in the images of Durban-based photographer Bobson Sukhdeo Mohanlall in which subjects creatively combine western and local forms of fashion, in those of John Liebenberg which record the self-styling of migrant workers in Namibia, also in the photography of Nontsikelelo ‘Lolo’ Veleko, which documents street fashion in post-apartheid South Africa. Ethnic identity is addressed in the fashionable knitwear of Laduma Ngxokolo who designs pieces which reflect Xhosa beadwork heritage, in Thabo Makhetha’s womenswear brand which incorporates Basotho blankets inspired by the designer’s Sotho heritage, as well as in the potential tension between ethnic and sexual identity depicted in an acquired artwork by Rotimi Fani-Kayode.

Diaspora

Living in diaspora generates new identity positions and cultural forms, which the Collecting Panel wanted to see reflected in the new collection. After moving to the UK in 1959, Ghanaian photographer James Barnor sought out black models to feature on the cover of Drum magazine, a South African publication with a pan-African readership. The museum acquired Barnor’s iconic shots of Marie Hallowi and Erlin Ibreck, important documents of Britain’s increasing diversity in the post-war period. In 1997, London-based photographer Eileen Perrier created Red, Gold and Green, a series of portraits of her Ghanaian family members, some of which have been acquired by the Museum. Perrier has said, ‘I was born and raised in London but come from a mixed cultural background of Ghanaian and Dominican descent, and this has presented me with questions around, placement, cultural identity and diversity’.

The museum acquired Yoruba wedding outfits that reflect the trend among diaspora couples for combining western ‘white wedding’ looks with outfits in Nigerian fabrics and styles, as well as garments and testimony which reflect the unique personal style of two Brighton-based musicians: Saidi Kanda and Musa Mboob.

Postcolonialism, Pan-Africanism & Resistance

The museum’s historic holdings of African textiles date to the period 1880 to 1940. It is essentially a colonial collection and so the fact that the rate of acquisition slowed from 1940 is unsurprising, given the building momentum towards independence which would be achieved by many African nations in the 1960s. The Collecting Panel wanted the Museum to acquire objects and images which would document the political changes underway. Some of these are captured in a number of campaigning T-shirts collected by the museum, as well as in the sweatshirt of Charles Makhuya, a member of Zimbabwe People’s Revolutionary Army, which is accompanied by his collection of badges and political pamphlets. The collection also reveals the extent to which fashion reflected social and cultural change in the post-colonial period, including the reworking of traditional silhouettes and textiles, the increased use of fitted, tailored garments and the rise of the individual fashion designer. Many of the textile forms acquired by the museum, such as kente, dashiki and wax print have become important signifiers of a pan-African identity.

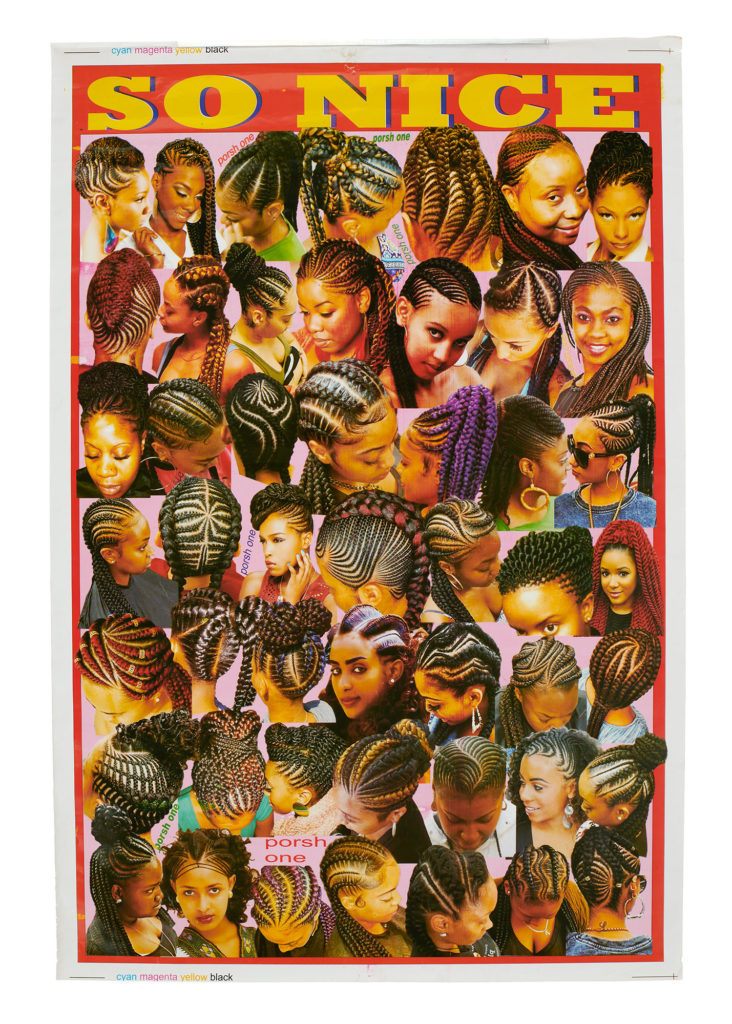

Accessories, Hair Styling & Make Up

As well as textiles and garments, Collecting Panel members wanted the museum to acquire other elements of fashionable styling including accessories and evidence of different approaches to hair and make-up. Some of these are captured in studio portraits acquired, but the museum also sought to acquire ‘complete’ outfits wherever possible. Sets of jewellery made from coral, agate and metal were acquired with a high-quality aso-oke outfit commissioned from a Lagos tailor and as part of several sets of fashionable garments from the personal collection of Saundra Lang. A set of posters collected in Ghana document contemporary women’s hairstyle fashions. The exhibition Fashion Cities Africa also provided an opportunity to collect contemporary accessories. Acquisitions made in this way include pieces by Maria McCloy, Adele Dejak and Ami Doshi Shah.

Gender & Age

Collecting Panel members noted that collecting activity should take a nuanced approach when it came to considering the role of gender and age in the making and wearing of textiles and dress. The questioning of conventional approaches to gender is apparent in a self-consciously androgynous outfit styled by Sunny Dolat which combines a slim, cotton kaftan by Katungulu Mwendwa with black scarf, clutch bag by Adele Dejak, sandals, and accessories by Ami Doshi Shah. Children and young people are often overlooked in collections of textiles and dress. A Hamidou Maiga studio portrait acquired by the Museum features a mother with a child seated on her lap, and efforts were made to collect textiles produced for use by children, including examples of Basotho Khotso blankets, a Wodaabe boy’s tunic and an outfit worn by an Eritrean child living in the UK.

Changing Trends

A key objective for the Fashioning Africa project was to challenge colonial modes of collecting which viewed textiles and dress as the outward expression of an unchanging, essentialised ethnic identity. The 400 images and garments acquired provide an insight into the extraordinary diversity and dynamism of changing fashions and styles across the African continent in the post-1960 period. There remain gaps. As a colonial collection, the museum’s historic collection of African textiles was strongly orientated towards Anglophone countries, and this bias proved hard to dislodge, although new acquisitions include examples of high-quality kaftans and a djellaba made and worn in 1970s Morocco, contemporary womenswear by Said Marouf, and artwork by UK-based Moroccan artist Hassan Hajjaj. While project activity has come to end Brighton Museum will continue to seek opportunities to make strategic acquisitions to build and develop the collection.